Another week, another new big-budget Hollywood movie that condemns God as unjust and uncaring. And it’s not just Hollywood. We hear it more and more in schools. In the marketplace. From unbelieving friends and family. How do you respond?

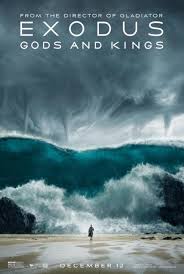

Another week, another new big-budget Hollywood movie that condemns God as unjust and uncaring. And it’s not just Hollywood. We hear it more and more in schools. In the marketplace. From unbelieving friends and family. How do you respond?First, we can gently ask about the inconsistency of condemning God. It’s stunning that you can walk into American theaters this week and see a movie, Selma, that shows the pain and loss of people suffering from the consequences of slavery based on race.Then you can walk next door to see Exodus: Gods and Kings . In case you hadn’t heard, in Ridley Scott’s version the most sympathetic character in Exodus is Pharaoh, a ruler with absolute power, who refuses to release a people he has enslaved…BASED ON THEIR RACE…and the God who delivers them is pretty much condemned as a terrorist.Pharaoh Ramses has condemned the Hebrews to lifetimes of harsh labor, and even in the face of nine terrible plagues he will not let them go. Finally, after the 10th plague he confronts Moses, clasping the dead body of his son in his arms, crying out, “What kind of a god does this? What kind of a fanatic follows such a god?”

Dr. Brian Matson reviewed the movie and nailed its glaring flaw: The only character in the story who is utterly unsympathetic is God. “Essentially, everyone in this film is horrified by Yahweh. Including Moses…’Yahweh’ is personified in the person of an 11-year-old boy. An utterly unlikeable, unsmiling, adolescent, impertinent, bloodthirsty, and vengeful brat. Everybody’s nightmare of what their kids might become as teenagers. God as Dylan Klebold, complete with the bloodlust.”

As a movie Matson gives it an “F” because the movie offers no motivation for Moses. Why WOULD he follow such a fanatic? Why would anybody? Scott has subordinated the integrity of his own movie to his antipathy for the God of the Bible.

This condemnation of God reminds me of CS Lewis’ famous essay, “God in the Dock,” where Lewis wrote, “The ancient man approached God (or even the gods) as the accused person approaches his judge. For the modern man the roles are reversed. He is the judge: God is in the dock. He is quite a kindly judge: if God should have a reasonable defense for being the God who permits war, poverty and disease, he is ready to listen to it. The trial may even end in God’s acquittal. But the important thing is that Man is on the Bench and God in the Dock.”

This was the situation in Lewis’s day. But times have changed. God is still in the Dock. And man is still the judge. But he is no longer a kindly judge. He seems increasingly less willing to listen to a reasonable defense for God permitting or using war and bloodshed to accomplish his purposes.

If I could have a cup of coffee with Ridley Scott I would try to raise this tension: Mr. Scott, is delivering people from slavery based on race right or wrong? Can you admire Dr. Martin Luther King, who was an ardent follower of Jesus, the Son of God, and condemn God for delivering another people from slavery based on race?

Perhaps he would make the case that Dr. Martin Luther King condemned the use of violence to accomplish his goals. By comparison, God inflicted incredible pain and loss of life on the Egyptians to get them to set the Hebrews free.

Yes, but Mr. Scott, Surely it’s possible that God knew far more than we do about the heart and motivation of the Egyptians. We have a pretty good historical precedent to show us that when a ruling people profits from the slavery of an oppressed people they will not set them free without bloodshed.

The Hebrews, had they risen up against Pharaoh, would have faced slaughter and terrible casualties, maybe annihilation. Imagine the American slaves with their pitchforks and machetes taking on the cannons and guns of the Confederate army. Even in Dr. King’s nonviolent struggle to sit at the front of the bus or at the lunch counter with whites, it still cost lives.

So maybe God, who knows the hearts of men, knew what it would take for Pharaoh to finally relent with the least amount of bloodshed possible. Maybe he knew how impossibly arrogant Pharaoh and his people were and knew it was the best way to humble them enough to insure they did not again pursue the Hebrews in the wilderness or as they settled into the land of the Canaanites. Actually Pharaoh did pursue them into the wilderness. God had to shed more blood to get him to ultimately relent.

If we consider all we know about the Egyptians and Hebrews compared to everything there is to know about that period in history and the thoughts of people’s hearts, isn’t it possible we don’t know nearly as much as God did? Maybe we don’t know enough to judge God.

CS Lewis would move the discussion closer to the heart. From his “God in the Dock” essay he might challenge hypocrisy in another way. To those who believe they belong on the bench and God belongs in the Dock, he would gently probe their own qualifications to be the judge. So you live such a moral and compassionate life that you never struggle with “conceit, spite or jealousy”? “Cowardice or meanness”? What about indifference to the suffering of others?

God cares far more about suffering than we do. God is “near the broken hearted” (Psalm 34:18). He hated the way the Canaanites and then his own people burned their babies in the fire as an act of worship, something “I did not command them, nor did it enter into my mind, that they should do this abomination” Jeremiah 32:35. That is one of the main reasons he gave for allowing the Hebrews to destroy the people of Canaan, and then allowing the Babylonians to turn around and destroy and deport the Jews.

If God allows a life to be taken we can trust that it will be just. Especially when we see his track record of allowing lives to be taken in order to save other lives. That is the beauty of the gospel. He allowed the life of his innocent Son to be taken by people who struggled with conceit, spite, jealousy and meanness so that we might have a life of blessing and forgiveness when we come to him by faith.

Well said! The inconsistencies of the modern secular mind are staggering. Another Lewis quote goes something like, “God loves us too much not to allow us pain…”

Pain has accomplished such great good in my life. Thanks for commenting, Lori.